When we began building the first four rooms. Eugene, our Kerala mud-expert architect, introduced us to rammed earth. This is a system of using shuttering and compressing the mud into this. However both because this was not traditionally used in this area so people were not familiar with the appropriate mud mix and also because our walls are sloping so it would have involved the making of complex and somewhat excessive shuttering, we went instead with the local method of slapping on layers of mud by hand—approximately a foot at a time. Working on several rooms together meant that each layer of mud had time to dry before applying more, as we worked from one cottage to the next.

Much of the mud work was done by women

Much of the mud work was done by women

Both men and women were involved in the construction and indeed several of both stayed on to re-train in other capacities and are still with us.

The lintels were locally hewn stone and they were levelled in traditional manner with a pipe of water. Only once we had a problem when the stone laid across a wide window had too much wet mud piled on it too quickly and it cracked under the weight. Fortunately this was easy to repair since it only required a new stone and more mud applied over a longer time period.

The environment is rich with termite communities. However we were not keen for these to infect our mud walls!

The environment is rich with termite communities. However we were not keen for these to infect our mud walls!

Since termites are ubiquitous and numerous in this area and we wanted to avoid toxic pesticides to keep them from our rooms, on Golak’s advice we applied a tar layer between the stone foundations and the mud above. We had also obtained some natural plant based anti-termite liquid from a company in Bangalore, Osolin, which has helped too.

Grass roofs that help to keep our cottage rooms cool

Grass roofs that help to keep our cottage rooms cool

For the roofs of these first four rooms we laid corrugated tin sheets to ensure waterproofness and on this was laid a bamboo frame on which the thatch grass is tied. The grass and skill for this came from neighbouring Rajasthan. This area of MP uses a different grass, Sachharum spontaneum (the main one growing at the Sarai) and a more casual design that does not last as long as the expert layered roofs that Chottu Ram and his crew crafted. They use Saccharum munja, a grass also used for baskets, rope and medicine. Their roofs last well for five or six years. We are now growing our own Munja on a plot of land nearby across the river.

For the second group of four cottages, while the grass roof remained the same on the outside, the under layer changed. We had learnt that small creatures like squirrels could run up and down between the thatch and the tin and create a disturbingly load noise! We therefore changed to a ferro-cement cover. This is a method which uses a steel wire mesh and allows for less cement to be used since only a thin layer is require as the wire mesh provides the requisite strength. Inside, this was given a white lime wash. Support beams were eucalyptus grown in a nearby nursery.

The ferro-cement roof underconstruction. This was a new method for our local builders.

The ferro-cement roof underconstruction. This was a new method for our local builders.

With the roofs up we could move to working inside the cottages. We had hoped to continue avoiding concrete and use lime, lusting after the wonderful soft finish of the Araish surfaces to be seen in old palaces of India, similar to Moroccan Tadelakt. However this process takes several months of crafting and drying and we did not have so much time available before our first guests were arriving. However a joyful (excuse the pun) miracle occurred thanks to Eugene. He introduced us to K A Joy and his team. They came from a small village in Kerala and practised a trade that had apparently originated with Italian priests taught to their forefathers and practised only by the families of this one area. They used cement but in a completely original way that not only allowed large areas to be covered without cracks but that achieves a close echo of the softness and coolness of araish.

The first cottage’s floor and edging

The first cottage’s floor and edging

The final thin layer of white cement was coloured with natural mineral oxides and we had much fun selecting and mixing these. The final result was always something of a surprise since a small test amount would never quite be the same as the larger space and besides it would change with drying and polishing.

We looked to nature for our colour inspiration.

We looked to nature for our colour inspiration.

Had we had more time and funds, there was no end to the floor patterns we might have enjoyed, such was their skill. But we had to content ourselves with a couple of dragonflies decorating a built-in table surface above two sitting areas.

There was one unexpected difficulty of the floor artistry. They required a large amount of newspaper for drying the cement. Not a big issue in a country of kabadiwallahs (waste vendors or recyclers) where old newspapers could be bought by the kilo. However the problem was that in our remote rural area there was little demand for, and therefore little waste of, English language newspapers and apparently the vernacular press papers used a different ink that could stain the floor if used! We found ourselves carrying kitbags of old newspapers on the train from our home in Delhi!

Some of the early bathrooms were cemented by a team from Goa where we had seen bathrooms that we admired. However they did not have the attention to detail that Joy did and we are still disconcerted by being able to make out a footprint in the colour of the floor! Fortunately only visible to a perfectionist’s eye so overlooked by most of our guests!

With the cottages well on the way to completion the Baithak took our attention. This was to be the main communal area for sitting and dining. We had chosen the highest point of the land with a wonderful 180’ view over the river and planned for it to be an open structure to take best advantage of the views and our fresh clean air.

Panna sandstone has the most beautiful and delicate soft hues of pink, amber and a pale sandy beige. We were fortunate to have met Swamideen, a painstaking craftsman, from a nearby village whose hand and hammer shaped the stones for our pillars and steps. He and the rest of the team skilfully wove them together with our lime mortar, some to roof supporting height and others part way to be completed with thick wooden columns carved in an adapted local style from neem (Azadirachta indica) and arjun (Terminalia arjuna).

Neem and arjun carved pillars

Neem and arjun carved pillars

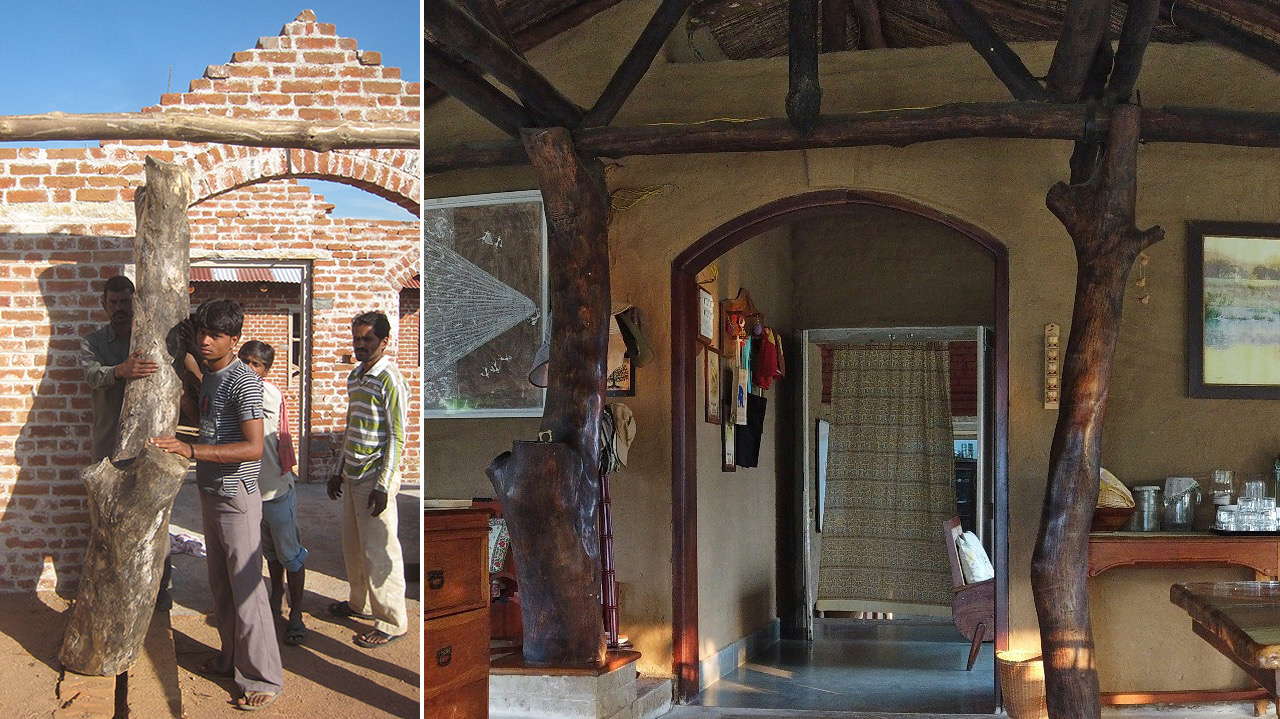

Another example of how the design changed as we built was in the transformation of two stone pillars to completely wooden supports. A neighbouring villager said he had a fallen tree on his land and would we like to buy and remove it for firewood. We agreed and hired a tractor to pick it up. However on its arrival at the Sarai, we found its trunk was thick and beautiful and far too good for firewood. We forewent two stone pillars on either side of the archway to the pantry and kitchen for these tree trunks; the character this gives makes them look as though they were made for that position.

Our ‘fire wood’ pillars

Our ‘fire wood’ pillars

We had seen some beautiful mud relief work on the walls of an old house in one of the nearby villages and were very keen to feature this on the internal wall of our sitting and dining area within the baithak. However though we asked around widely, we could find no one able to do such work. This wall was apparently around 100 years old and sadly the skill was no longer available.

100 year old mud relief work in a house at Dhamna village

100 year old mud relief work in a house at Dhamna village

We settled for plain mud plaster and adorned it with wonderful artwork—on one side a beautiful giclee print on canvas of a Panna landscape with tigers by the wonderful Welsh artist, Bas Evans, who had visited us in the tiger reserve during Raghu’s study time; on the other, a large Warli painting by Sadashiv Mashe of a fishing net so intricately done that you really have to peer closely to determine whether it is a net stuck to the canvas or only paint!

The floor of the Baithak is also mud although we mixed a little cement (around 5%) into the base for stability. For the outer layer we again looked to vernacular architecture—gobar. Gobar is cow dung and while this may seem strange to a western or urban audience, it is well known in villages to make a wonderful and versatile finish that not only has a lovely feel to walk on (never warm nor cold) but it is anti-bacterial and deters insects and small creatures so is a really healthy choice. It is also a wonderful option as you may spill your coffee or wine on the ground with impunity since it soaks in, dries fast and leaves no stain. However it does have to be resurfaced every couple of weeks or so but can be done within a couple of hours. We use the same flooring for the cottage verandahs.

The newly done gobar covering

The newly done gobar covering