Last year, Joanna and I visited Ladakh after almost a decade. Rumbak, now a world-famous site for snow leopard sightings, was our home from the late eighties to early nineties. Raghu came here to study snow leopard for my PhD degree, and continued to work in the area up until 2000 after I finished my thesis and less frequently until 2008. During all this time Joanna was there photographing and filming Ladakh wildlife.

So, the trip last year for both of us was a journey down memory lane, it was a short and rushed trip but an eye opener to see changes that have taken place recently. I had joined Joanna to attend the Tiger Tops alumni meet, a gathering of several friends we knew. I am glad that we took this trip to Ladakh, because it rekindled our emotional connection with Ladakh.

We had heard and seen pictures of Leh town, so were not so surprised to see the development there. We did appreciate the pedestrianised main street but Leh and its satellite village/towns now face the same environmental problems that most of our popular tourist destinations do in India. Somehow in a rush to develop tourism in an area, we end up destroying the destination itself. This is a typical story, and development in Leh seems to have followed the same path. It seemed a shame as in the early days there had been many with environment sensibility and it could have trodden a different path; for example, Leh inhabitants had been some of the first in India to discourage plastic water bottles and instead refill at the Dzomsa store (then and now). Sadly, now bottle rubbish abounds. We hope the administration will make corrective measures and also hope that it is not too late.

Change was in the air/Changing times

Rumbak village in the late 1980s (above) and 2019 (below)

Rumbak village in the late 1980s (above) and 2019 (below)

But some of the changes in rural Ladakh were unexpected. We found just enough time to make a short visit to Rumbak and meet the families and friends we had lived with for years. Rumbak looked prosperous and in better shape, many of the houses had become double storied structures and were well kept. In 1985 when we first arrived here, only one house had a first floor. Even the interiors looked modern this time, especially the kitchens with good adaptation in harmony with the traditional.

Ladakhi kitchen

Ladakhi kitchen

The surprise came, when we started talking. Earlier the village economy was based on livestock and agriculture. That has changed now. Rumbak, and the houses at nearby settlements of Yuruche and Zingchen, do not keep sheep and goats anymore and we even saw many crop fields left fallow. The younger generation now finds employment in the town and earn better wages than is possible in these higher altitude places.

Older generations do not have energy to look after livestock and crops as they used to, so only what is manageable is cultivated. Now that the road is reaching the village, families have bikes and cars and can drive from Leh to Rumbak in a couple of hours. Apparently, the younger family members do come to extend helping hands but not enough to keep up with all the old traditional practices.

Crossing the Spituk plain before the advent of the road. Wood from Rumbak being carried to Leh on dzos.

Crossing the Spituk plain before the advent of the road. Wood from Rumbak being carried to Leh on dzos.

While driving on this road, we remembered the walk we used to take on these vast alluvial fans from Spituk to the Rumbak valley entrance: it used to take three to four hours and was quite tiresome since for hours the landscape hardly changes as one walks parallel to the Indus. It was monotonous, walking in one direction and for so long that in winter one could get sunburned on one side of the face while icicles formed on the other shaded side! It was only when we reached the confluence of Rumbak and Indus that excitement began. Just before the beginning of the valley, there is a Lato, the site where locals pile stones and horns and offer whatever they had to the guardian spirit of the valley. It is here at the Lato, we would break for rest and to scan the slopes to spot the Urials. This was also an opportunity for my last sip of “Chhang”. I had promised myself not to drink alcohol in my study area and the Lato was the boundary. The horseman and others knew this and always left a share for me there. On our recent visit we drove past this Lato reminding us of old times; it was sad to see it looking ignored, no new horns in the pile and even the stone structure was looking tired. A definite sign of changing times.

Walking on the new Rumbak road still under construction

Walking on the new Rumbak road still under construction

We were glad that the last bridge on the road to Rumbak was still under construction so we could not drive all the way. We needed to walk the last few kilometres to the village. Seeing the JCB working on the road was a disturbing sight, having known the area in its pre mechanisation days. But these roads do bring remote villages much closer to health care and other support systems, which, in their absence, are almost inaccessible except by foot and pony.

As we walked on the dusty track created by the JCB and road makers, amazingly we found fresh sign of a snow leopard mother with cubs. We were so excited to find that these building activities had not driven away such shy animals and that they were bold and relaxed enough to take a walk on this newly constructed road right past the JCB parked for the night. It was a most encouraging sign and one that allows hope that recovery from the temporary disturbance will be quick.

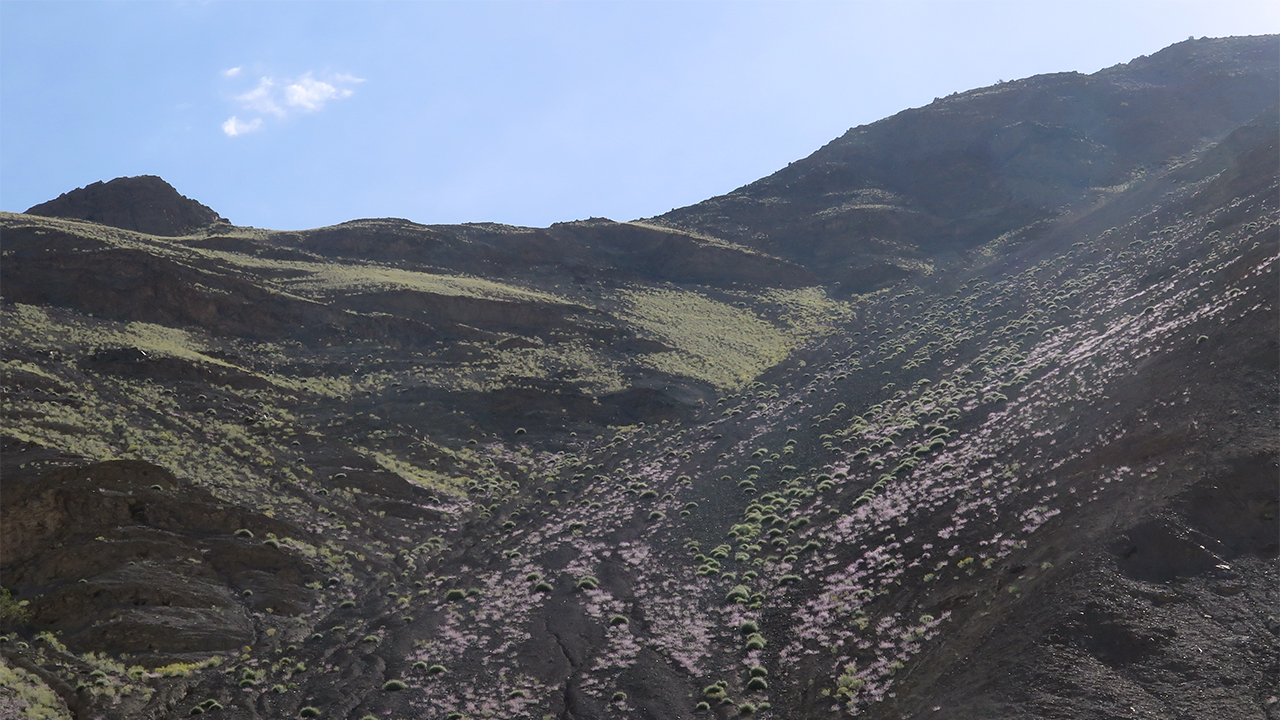

Rumbak valley slopes with a rich covering of vegetation

Rumbak valley slopes with a rich covering of vegetation

Our first reaction looking around as we approached Rumbak village was that we have never seen the slopes looking so lush. Whether this was from the increased summer rainfall or reduced livestock we could not know but it made us wonder how these changes would affect the ecology and ultimately the snow leopard. If we look at articles on snow leopards, one common theme is livestock / wild prey competition; the view tends to be that grazing by livestock limits wild prey abundance and that livestock depredation is a major threat to snow leopard. The common notion is that there will be growth in wild prey population as the domestic biomass reduces and that this will bring happy times for snow leopards. But will this actually happen? Will the blue sheep population explode and will this break the snow leopard density dependence equilibrium? I decided to share these questions with some of my snow leopard expert friends, to canvas their opinions.

Bharal, blue sheep on the lush slopes of Rumbak valley

Bharal, blue sheep on the lush slopes of Rumbak valley

In our experience, depredation on livestock by snow leopard was never a major threat for Rumbak. In our time there, none of the villagers viewed snow leopards in that way. In fact, there were fewer losses to snow leopard than to wolves. Ladakh is had a traditional regulatory mechanism to deal with wolf menace, if it became an issue. Wolf traps were part of this system, but most years these traps were left dormant. In our conservation planning we feel we should recognise these traditional practices evolved to minimise conflict and therefore helped co-existence. Since most of the year peace prevails with both snow leopard and wolves, and populations of both were surviving happily, there seems little need to change tradition, unless we have a better mechanism to address the same issue.

The changes we saw and the ecological questions these were raising, triggered thoughts and memories. Articles we read often seem based on assumptions developed from outside the region and lack a local historical perspective. This seemed a prod to put pen to paper, and indeed until the pandemic intervened, we had planned to spend 2020 summer in Ladakh re acquainting and updating ourselves with the area and beginning a book of our experiences and Raghu’s research. These blogs are a step in that direction, so do please comment for improvement!